Paper: Lagrangian Fluid Simulation with Continuous Convolutions

In this article, I’ll present the paper “Lagrangian Fluid Simulation with Continuous Convolutions” by Ummenhofer et al. (2020).

The problem

Convolutions are an integral part of modern neural network architectures. A convolution is an operation that moves a mask over an input grid and measures how well the mask fits for each grid point. Grids can have an arbitrary number of dimensions. Examples for data in grid form are audio streams, images and volumes represented by voxels.

Sadly, not all data is arranged in a grid. Especially in the world of measurements and simulations, other representations are more suitable. Many possible solutions for convolutions have been proposed in the past to deal with meshes or point clouds.

The solution

Ummenhofer et al. try to generalize the concept, such that it is applicable to point clouds. In their example, they apply the technique to learn the physics of Lagrangian fluid simulations.

They define the traditional discrete convolution (eq 5) as:

\[(f \ast g)( \boldsymbol{x} ) = \sum_{\boldsymbol \tau \in \Omega} f(\boldsymbol x + \boldsymbol \tau) g(\boldsymbol \tau)\]Note: To be exact, this is the definition of a correlation. A convolution rotates the mask before applying it, but we will follow the paper’s lead and drop the distinction.

The proposed new continuous convolution (eq 7) is:

\[(f \ast g)(\boldsymbol x) = \frac{1}{\psi (\boldsymbol x)} \sum_{i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)} a(\boldsymbol x_i, \boldsymbol x)\ f_i\ g(\Lambda(\boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x))\]Let us try to understand the individual parts of the equations. We start by defining the symbols.

Symbols

\(f\): input function

The input we want to match against, i. e. an image, a soundtrack …

\(g\): filter function

Often also called a kernel. The pattern we are looking for in the input.

\(\boldsymbol \tau\): shift vector

Usually, this vector is defined as a “local” vector relative to the filter function. Often, \(\boldsymbol \tau = \boldsymbol 0\) means the center of the kernel, while the components are in the range \([-N, N]\) to cover the entire kernel.

\(\Omega\): set of used shift vectors

This usually maps to all entries of the input kernel.

\(\mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)\): neighborhood set of \(\boldsymbol x\)

The set of all points around \(\boldsymbol x\) within a radius \(R\).

\(a\): density normalization

This component is inspired by “Particle-Based Fluid Simulation for Interactive Applications”, Müller et al. (2003). There, it is called a “smoothing kernel”. It gives points close to \(\boldsymbol x\) a higher weight, while points further away have a smaller impact. The original paper proposes three different kernels for different situations. Ummenhofer et al. decided to use:

\[a(\boldsymbol x_i, \boldsymbol x) = \begin{cases} \left (1 - \frac{ || \boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x ||^2_2 }{R^2} \right )^3 & \text{for } || \boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x ||_2 < R \\ 0 & \text{else} \end{cases}\]\(\psi\): normalization function

\(\psi\) is a consequence of introducing \(a\), which applies an “arbitrary” scaling to the final result. \(\psi\) gives the option to revert the scaling back, for example by using

\(\psi(\boldsymbol x) = \sum_{i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R} a(\boldsymbol x_i, \boldsymbol x)\).

We could move it inside the sum to demonstrate the way it normalizes the weights:

\[(f \ast g)(\boldsymbol x) = \sum_{i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)} \frac{ a(\boldsymbol x_i, \boldsymbol x) }{ \sum_{i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)} a(\boldsymbol x_i, \boldsymbol x) } f_i g(\Lambda(\boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x))\]\(\Lambda\): Ball-Cube Mapping

When implemented, they store \(g\) as a grid and use linear interpolation between the stored grid values. Somehow, the stored grid values need to be mapped back to a ball. The transformation \(\Lambda\) is taken from A bi-Lipschitz continuous, volume preserving map from the unit ball onto a cube, Griepentrog et al. (2008) and does exactly this.

Here is an animation to give an intuition for the transformation \(\Lambda\):

Generalizing the Convolution

Now that we understand all parts, let us try to understand how to get from one formulation to the other. I like to introduce one change at a time, so we can observe the changed effects better (even if it introduces some imprecision in the math).

\[(f \ast g)(\boldsymbol x) = \sum_{\boldsymbol \tau \in \Omega} f(\boldsymbol x + \boldsymbol \tau) g(\boldsymbol \tau)\]First, we observe, that \(\boldsymbol \tau \in \Omega\) can be replaced with something more generic: \(i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)\). We can use \(\boldsymbol \tau = \boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x\).

\[(f \ast g)(\boldsymbol x) = \sum_{i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)} f(\boldsymbol x_i)\ g(\boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x)\]Further, we’ll use \(f_i = f(\boldsymbol x_i)\) and we can introduce our radial mapping \(\Lambda\).

\[(f \ast g)(\boldsymbol x) = \sum_{i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)} f_i\ g(\Lambda(\boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x))\]This formulation allows us to map a ball to a cube and iterate over individual points within the ball. Assume, we want to move the ball around. It should be clear, that, while moving, points will enter and leave the ball. This will cause the resulting field not to be continuous. We want the influence of points to increase and decrease depending on their distance. So we can add the last piece: \(a\), which controls the points’ impact. \(\psi\) is just an explicit way of handling normalization.

\[(f \ast g)(\boldsymbol x) = \frac{1}{\psi (\boldsymbol x)} \sum_{i \in \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x, R)} a(\boldsymbol x_i, \boldsymbol x)\ f_i\ g(\Lambda(\boldsymbol x_i - \boldsymbol x))\]Note that in Appendix 4, they discuss alternative window functions for \(a\). The results suggest that not using a window function at all also delivers “plausible” results and might be suitable for other applications. They conclude, that finding a better window function is a possible direction for future research.

Interface

We now understand the math behind the continuous convolutions. Ummenhofer et al. also define an interface for it in chapter 5.1 “Network Architecture”:

\[F = CConv(S, X, G, R)\]- \(S = \{s_1, ..., s_M\}\): A set of input particles, each one defined by a position and a feature vector.

- \(X = [\boldsymbol x_1^{n*}, ..., \boldsymbol x_N^{n*}]\): A list of intermediate positions where the convolution should be evaluated.

- \(G\): A 5D array storing all filters in the layout \([width, height, depth, ch_{in}, ch_{out}]\).

- \(R\): Radius \(R\) of ball to consider.

- \(F = [\boldsymbol f_1, ..., \boldsymbol f_N]\): A list of the resulting feature vectors for each intermediate point position.

As mentioned in the paper, note that for a traditional convolution, the size of the used filter defines the receptive field. Using \(R\) and \(G\) decouples the resolution from the receptive field. Changing \(G\) does not influence the receptive field, while changing \(R\) has no effect on the resolution. I wonder what tricks become possible with this decoupling. Maybe training high-resolution convolutions or adapting the size according to the point density?

That’s it. We now understand continuous convolutions. Let us see how Ummenhofer et al. applied it to fluids.

Application: Fluids

The goal is to train a network with fluid simulations, such that it can apply the physics of fluid mechanics to new situations, hence replacing the costly simulation computations.

The Navier-Stokes equations for incompressible fluids are well studied:

\[\frac{\partial \boldsymbol v}{\partial t} + \boldsymbol v \cdot \nabla \boldsymbol v = - \frac{1}{\rho} \nabla p + \nu \nabla^2 \boldsymbol v + \boldsymbol g\] \[\nabla \cdot \boldsymbol v = 0\]Lagrangian fluids try to solve these equations by thinking about particles, blobs of matter, that move around and follow these equations.

Our target is to define a learnable pipeline, that allows us to integrate a given time step of a fluid simulation.

More formal:

Input: \(X_n, V_n\)

Output: \(X_{n+1}, V_{n+1} = advance(X_n, V_n)\)

The paper defines the \(advance\) function as follows:

-

First, it applies Leapfrog integration to the input.

\[V_n^* = V_n + \Delta t A_{ext}\] \[X_n^* = X_n + \Delta t \frac{V_n + V_n^*}{2}\]The acceleration \(A_{ext}\) allows us to set external forces, like gravity. As mentioned in the paper, this integration step lacks any interaction between the particles.

-

Dynamic and static particles need to be reduced to feature vectors.

The feature vector for each moving particle \(i\) at time step \(n\) is:

- constant scalar 1

- velocity \(\boldsymbol v^n_i\).

- viscosity \(\nu_i\)

The paper uses a tuple notation to indicate, that position is not used as feature.

\[p^{n*}_i = (\boldsymbol x^{n*}_i, [1, \boldsymbol v^{n*}_i, \nu_i])\]Static particles \(s_j\) are characterized by their surface normal:

- Position \(\boldsymbol x_j\)

- Surface normal \(\boldsymbol n_j\)

Written as:

\[s_i = (\boldsymbol x_j, [\boldsymbol n_j])\] -

The integrated values, together with additional features, are then fed to the network. Ummenhofer et al. call the function implemented by the network \(ConvNet\). It is tasked to learn a residual position.

\[[\Delta \boldsymbol x_1, ..., \Delta \boldsymbol x_N ] = ConvNet(\{ p_1^{n*}, ..., p_N^{n*} \}, \{ s_1, ..., s_M \} )\]Its input is a list of intermediate point feature vectors and a list of static particle feature vectors. For each particle, it returns a correction for the position. We expect the position correction to consider all particle interactions, including the collision handling with static particles.

-

The correction is applied by adding it to the particles’ intermediate positions and computing the new velocity as the position difference between time step \(n\) and \(n + 1\):

\[\boldsymbol x^{n+1}_i = \boldsymbol x_i^{n*} + \Delta \boldsymbol x_i\] \[\boldsymbol v^{n+1}_i = \frac{ \boldsymbol x_i^{n+1} - \boldsymbol x_i^n } {\Delta t}\]

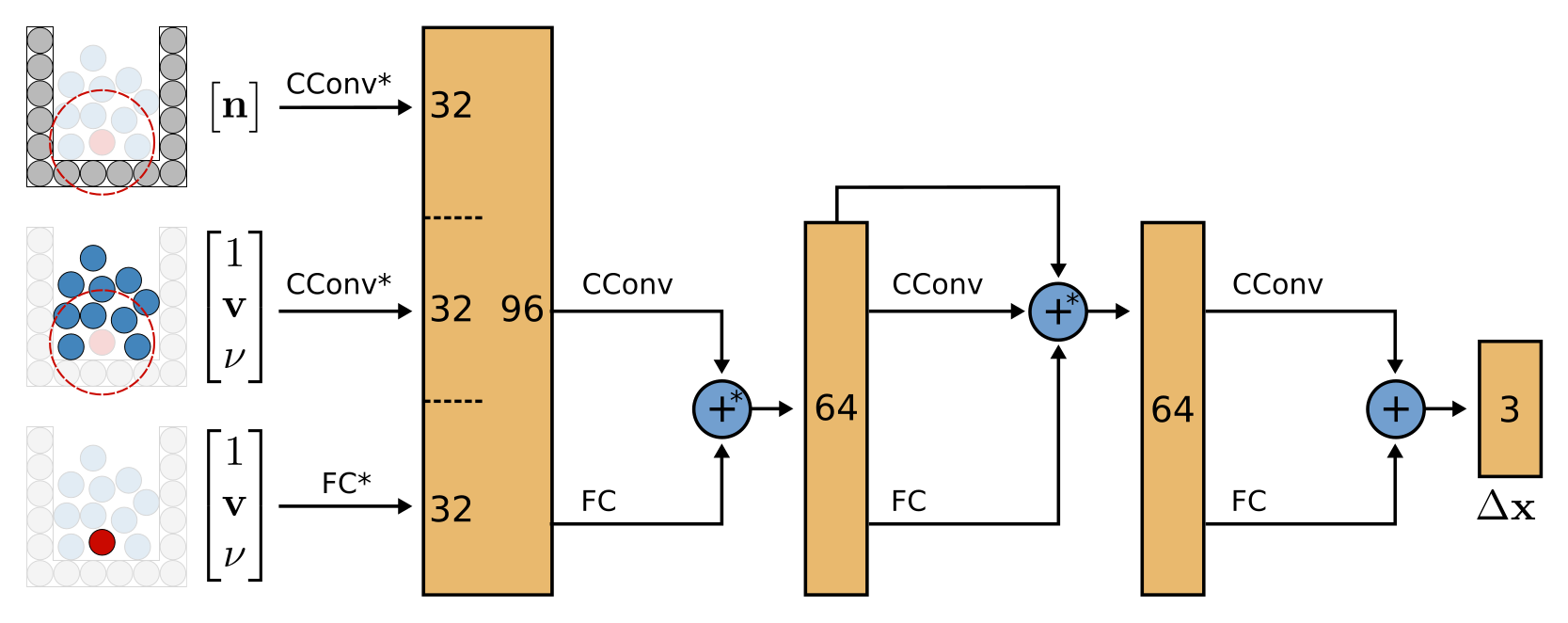

ConvNet: Network architecture

The network consists of four distinc levels.

The first level converts the different feature vectors into feature vectors of size 32.

There are three distinct cases: static particles, dynamic particles and the particle at the center of the convolution.

-

In the first case, convolutions are performed at all positions of dynamic particles \(D\), but only the feature vectors of static particles \(S\) are used.

\[CConv(D, S, G, R)\] -

In the second case, convolutions are performed at all positions \(x_i\) of dynamic particles \(D\), but only the feature vectors of dynamic particles, except the feature vector for particle i at the convolution center, are considered.

\[CConv(D, D \backslash \{p_i\}, G, R)\] -

The last case applies a bunch of fully connected layers to each dynamic particle’s feature vector.

The second level then applies another continuous convolution and some fully connected layers to reduce the feature vectors from 96 to 62 and adds them up.

The third level adds a residual channel and the last level reduces everything to the desired three residual values \(\Delta X\).

The authors note that they use only filters of spatial resolution [4, 4, 4] and a radius of 4.5 times the particle radius \(h\). Checking Appendix 3, they mention using DFSPH with \(h = 0.025 m\)

All in all, a reasonable architecture that unifies the different types of feature vectors to a common size and then applies the continuous convolutions multiple times to get to the final output.

Network training

The defined loss is fairly straight forward:

\[\mathcal L^{n+1} = \sum_{i = 1}^N \phi_i ||\boldsymbol x_i^{n+1} - \hat{\boldsymbol x}_i^{n+1} ||^\gamma_2\]It makes sure that the correction returned by the network is close to the original simulation, i.e. the ground-truth position \(\hat{\boldsymbol x}_i^{n+1}\) is close to the predicted position \(\boldsymbol x_i^{n+1} = \boldsymbol x_i^{n*} + \Delta \boldsymbol x_i\).

\(\phi_i\) assigns each point a weight, emphasizing important points. The authors consider points at the surface and the boundary especially important, as they are crucial for the visual results. They propose to emphasize the loss for particles with fewer neighbors:

\[\phi_i = \exp \left( -\frac{1}{c} | \mathcal N(\boldsymbol x^{n*}_i) | \right)\]They choose \(c=40\), s.t. it is the average number of the neighbors across their experiments.

Using an exponential for \(\phi\) seems a bit aggressive at first sight, but works out when checked in detail:

Given a \(c\), we can assume that particles in the densest region don’t go far above some simple multiples like \(2c\) or \(4c\). Hence, we can assume that \(\phi\) will roughly be in the range \([\exp(-4)=0.018, 1]\).

\(\gamma\) is chosen to be \(0.5\), giving small particle motions more impact and so improving visual fidelity for small fluid flows.

One should note that the authors optimized over two time steps:

\[\mathcal L = \mathcal L^{n+1} + \mathcal L^{n+2}\]The authors generate a whole bunch of train and test scenes, check the paper for the details.

Results: Continuous convolutions

The improved performance for the continuous convolution is impressive compared to the other methods (table 1, table 4).

I hesitate to trust the distance scores. It looks as if the entire pipeline was created and optimized using their convolution formulation. If one would seriously consider another formulation, one would also optimize the hyperparameters. So, just replacing the convolution operation seems a bit unfair but I don’t blame them, as you can always do more.

Another thing I’d like to see at some point is how well the formulation does in other point cloud benchmarks (classification, segmentation, …) and other data sources (3D scans). Having such fine control over radius and resolution could prove crucial to speed up learning or to process more heterogeneous datasets.

One question, that pops up comparing it with traditional convolutions, is how to translate the concept of strides. A stride defines the movement of a kernel. Instead of applying it to every grid point, one can skip every other column and row, hence reducing the resolution. This is a very natural way of reducing a large set of feature vectors down to a single one, describing the entire grid.

Results: Simulating fluids

To quantify the results, the authors use this evaluation metric:

\[d^n = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i = 1}^N \min_{\boldsymbol x^n \in X^n} ||\boldsymbol{\hat{x}}_i^n - \boldsymbol x^n||_2\]For each particle from the ground truth, it measures the distance to the closest predicted point and averages all distances.

What properties does it have? If you play around with this small tool, you should quickly observe that the function is not symmetric as soon as points don’t match pairwise.

The metric will be low if every point in the ground truth has a predicted point close to it. As points can be “shared” as nearest neighbors, predicted points that are far away, can be “covered” by other predicted points.

Is it a problem for the interpretation of the results? Probably not.

The description of the training process and the demonstrated results are well documented in the paper. I think at this point, I let the author’s video speak for itself: Lagrangian Fluid Simulation with Continuous Convolutions (ICLR 2020), Youtube.

Conclusion

In general, the paper is well written and presents the method clearly. I do miss a bit a “cover” picture that encapsulates the paper’s achievement in one image, though the architecture overview comes close to it. Knowing that authors are always under pressure to meet the deadline, I would have loved to see some more qualitative results of other methods, especially as some methods achieved better scores than DPI-Nets (Table 1). At points, it feels like the continuous convolution deserves its own paper, diving deeper into its advantages and limitations as it incorporates such a fundamental operation.

All in all, I think Ummenhofer et al. have developed an exciting new method to simulate fluids easily and cheaply. I am thrilled to see where future research will lead to!